|

|

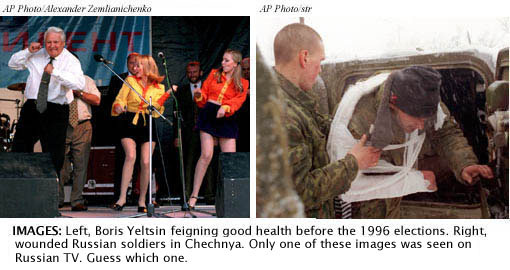

New York, March 27, 2000 --- During the

1996 Russian presidential campaign, many voters were swayed by TV footage of

Boris Yeltsin jiving with a dancer at a youth rally. Pro-Yeltsin stations

splashed the footage because they wished to project an image of Yeltsin as a

dynamic, youthful reformer. The TV image that helped assure Vladimir Putin's

victory in the March 26 election, on the other hand, was that of Russian

artillery blasting Grozny to rubble.

Both images demonstrate how the Russian government has used the media to deceive

their audience. The real story in 1996 was that Yeltsin was on the brink of

another heart attack, which sympathetic Russian journalists did not report.

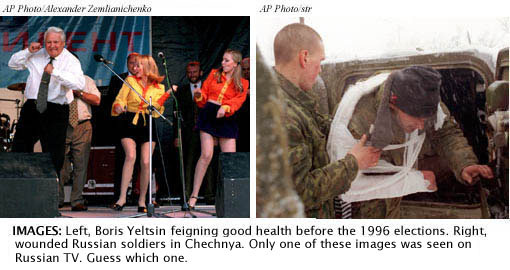

Today, the absence of objective reporting about the war in Chechnya, of which

acting president Putin is the architect, has kept the former KGB official's

popularity ratings high.

Throughout the conflict, virtually all Russian media have demonized Chechens and

highlighted Russian military successes. At the same time they have downplayed

the destruction of villages and cities, the plight of refugees, and allegations

of brutality and torture by Russian troops.

Independent Russian journalists worry that with so many of their colleagues

accepting the role of adjunct government flacks, the hard-won freedoms of the

post-Soviet era could be in jeopardy. Meanwhile, there are ominous signs that

independent journalism faces a bleak future under the Putin regime

Media barons

In Russia, media control confers enormous political power. Consolidation of

ownership was accelerated ahead of the parliamentary elections last December.

Today it is difficult to name a single Moscow newspaper or broadcaster that is

not directly controlled by one of three competing media conglomerates. One group

is headed by business tycoon Boris Berezovsky, who is close to the Kremlin.

Berezovsky controls the state television channel ORT and a number of influential

newspapers. Another is the fiefdom of Vladimir Gusinsky, who owns NTV, the major

private television station, and several publishing interests. The third is ruled

by Moscow mayor Yuri Luzhkov, who controls TV-Tsentr and a handful of newspapers.

"The media barons have their own goals and, naturally, if journalists want

to keep their jobs they have to go along with those views," says Sergei

Sokolov, deputy director of Novaya Gazeta, one of the few surviving

independent newspapers. "The oligarchs' views may not be so apparent when

things are quiet, but it only takes an election for it to become absolutely

clear which media group a particular paper or channel belongs to."

Media bias reached fever pitch during the December parliamentary election

campaign, when facts and balance lost out to slander and mud-slinging designed

to destroy candidates' reputations. Commentators such as Sergei Dorenko, who

anchors ORT's flagship political program, blatantly supported the pro-government

party and mercilessly attacked its rivals. Though Dorenko used perhaps the

greatest array of dirty tricks, almost all media put out openly biased material,

to the open dismay of a few major quality newspapers such as Segodnya and

Izvestiya.

Telling it like it is

Few Russian journalists even try to pretend that their reporting is not

influenced by the owner's political agenda. Moscow-based journalist Kirill

Byelyaninov, for example, works for both a Luzhkov television program and a

Berezovsky newspaper. He acknowledges a tacit understanding that certain

subjects are off-limits. "You basically know what's prohibited," he

says. "It's clear to all of us which camp the owner belongs to, and what

information is allowed. I cannot write anything concerning Berezovsky himself,

or his business partners or ventures, and of course I cannot touch the Kremlin.

With Luzhkov, I cannot write about Moscow or the city authorities."

It also works the other way--journalists are encouraged to attack rival barons

by any available means. "I dig up dirt on both," Byelyaninov says.

"If it's dirt on Berezovsky I put it in the program, and if it's dirt on

Luzhkov then it goes in the newspaper."

This willingness to skew coverage is partly a vestige of Soviet times, when

writing to promote a particular official or political line was part of the job.

In the glasnost years of the late eighties and early nineties, Russian

journalists briefly reveled in their ability to express truly independent views.

The 1996 presidential election proved to be a watershed, however, as most media

openly backed the Yeltsin campaign. NTV president Igor Malashenko, notably,

worked simultaneously as Yeltsin's campaign manager. In his own defense,

Malashenko argued that journalists had a duty to support the candidate who

seemed most likely to protect press freedom.

Most observers agree that overwhelmingly sympathetic media coverage played an

important role in Yeltsin's 1996 victory. Blatant media bias also contributed to

the pro-Putin Unity bloc's victory in December's parliamentary elections, and is

likely to help assure Putin's victory on March 26.

The almighty ruble

Naturally, money also plays a role. Politicians pay journalists to push a

particular line, and pay media executives to be invited on political programs.

As a result, the proverb, "He who pays the piper, picks the tune," has

become popular in media circles. "Journalists find themselves in a

situation where either they must serve their master like a dog on its hind legs

begging for a piece of meat, or be without work," says Pavel Gusyev,

chairman of the Union of Journalists and editor of the Luzhkov-controlled daily Moskovsky

Komsomolyets. "There are very few independent publications, and not all

journalists can work for one."

Today, press freedom is increasingly threatened by the government as well as by

the press barons. State pressure on media intensified after Putin became acting

president on December 31, 1999. Since then, the government has stepped up its

censorship of Chechen war coverage and continued subsidizing regional media

outlets in return for their support of government policies.

In January, Putin signed a new law transferring control of government subsidies

for regional newspapers from local politicians to the press ministry. The law

affects 2000 subsidized newspapers across Russia, and will act as a further

mechanism for central government control. This is particularly true in the

hinterland, where papers and broadcast stations are often dependent on local

administrators for everything from floor space to computers. Given that

subscriptions and advertising amount to a small fraction of local media's

operating costs, the subsidies are a crucial tool for influencing media content.

Cash is not the only weapon at Putin's disposal, however. The state controls

printing presses and has the power to issue and revoke broadcast and publishing

licenses. It can also exert pressure by ordering tax inspections, a weapon

frequently used by regional authorities to encourage friendly coverage.

At the national level, the government

maintains unhealthily symbiotic links with leading journalists, many of whom

glide comfortably from press jobs to government positions, and back again. If

anything, this trend has accelerated since Putin took office. In January, NTV

general director Oleg Dobrodeyev, who had helped build the channel's reputation

for balanced, professional news reporting, quit his job to run VGTRA, a vast

conglomerate of fully state-owned television and radio outlets. And Mikhail

Lesin, the head of the Press Ministry (set up last July to regulate all media in

Russia) has had a typically muddy past--a former state television official, he

was one of Yeltsin's top image makers, and is now an apologist for Putin's

scorched-earth media relations policy. Lesin has stated that he disagrees "with

the thesis that the state is more dangerous to the media than the media is to

the state. I believe quite the opposite."

Uncovering Chechnya

The Chechen military campaign has become Putin's political launching pad. "His

reputation to date has been founded on the bloody war in Chechnya, a fact which

by itself should ring alarm bells," says Yevgeni Kiselyov, the host of

"Itogi," ("Results") a leading political affairs program on

NTV. "Putin is a man of whom we know very little. Many people see him as

too pragmatic, and doubt his fundamental democratic convictions."

These doubts were partly fired by the Putin government's severe restrictions on

independent press coverage of Russian military activities in Chechnya. Coverage

of the current Chechnya campaign has been markedly different from the 1994-96

war, when most media outlets, notably NTV, reported the conflict courageously

and critically. This time around, few local media have opposed or even

challenged the official line. The independent newspaper Novaya Gazeta is

an exception, having devoted many column inches to the dearth of accurate

government information about the war. But there has been little eyewitness

coverage, partly because of the very real risk of being kidnapped by rebel

forces if you travel without Russian military protection.

Andrei Babitsky, a Russian national who works as a correspondent for the U.S.

government-funded Radio Liberty, was one of the few Russian journalists who

chose to flaunt Kremlin restrictions on Chechen war coverage. He traveled

independently through the war zone and sent eyewitness accounts of the impact of

the conflict on ordinary people. In January, Babitsky was arrested by Russian

authorities, beaten, and eventually released, following an international outcry,

after spending more than a month in captivity. He is still under close official

scrutiny, and is barred from leaving Moscow while his case is investigated.

Babitsky challenged the government monopoly of information by reporting from the

Chechen rebel side, which infuriated Russian authorities and led to his

detention. His treatment suggests that journalists who disobey the authorities

can expect to be branded "enemies of the state."

Babitsky notwithstanding, the Kremlin has successfully imposed an information

blackout in Chechnya, particularly on the sensitive issue of Russian military

casualties. By hiding the true casualty figures, the government has been able to

sell the war to its citizens, many of them already terrified by last fall's

apartment bombings in Moscow and elsewhere, which the government blamed on

Chechen separatists.

Acting president Putin also opened a government briefing center dedicated to

eliminating independent journalism about Chechnya. Even before Babitsky's arrest,

the center accused him of "conspiracy with Chechen terrorists,"

setting the stage for the government's insinuation that his coverage was suspect

and ran counter to Russia's national interests.

Policing the Web

Russian Internet service providers are required by law to link their computers

to the FSB, the successor to the KGB. Under an amendment signed into law by

Putin and taking effect from January this year, an additional seven

law-enforcement bodies have been authorized to monitor e-mail and other

electronic traffic. Technically, all these agencies are required to obtain a

warrant before examining private Internet communications, but local human rights

activists suspect they may not always bother with legal formalities. "This

is by definition a violation of the fundamental and constitutional rights of the

citizen," says Yuri Vdovin, deputy chairman of the St Petersburg-based

group Citizens' Watch. The Russian press has been largely silent on this issue.

Russians have good reasons not to trust or respect the press, but they are

nonetheless affected by what they read in the newspapers and watch on television.

As a result, the outcome of elections is greatly influenced by press coverage.

Vladimir Putin has shown himself adept at manipulating public opinion in favor

of his Chechnya campaign. During his first months in office, he has also

demonstrated a desire to exert more control over the lives of the country's

citizens. That makes sense for a man who spent most of his career in the KGB,

but it augurs badly for the future of independent journalism in Russia.

|

![]()